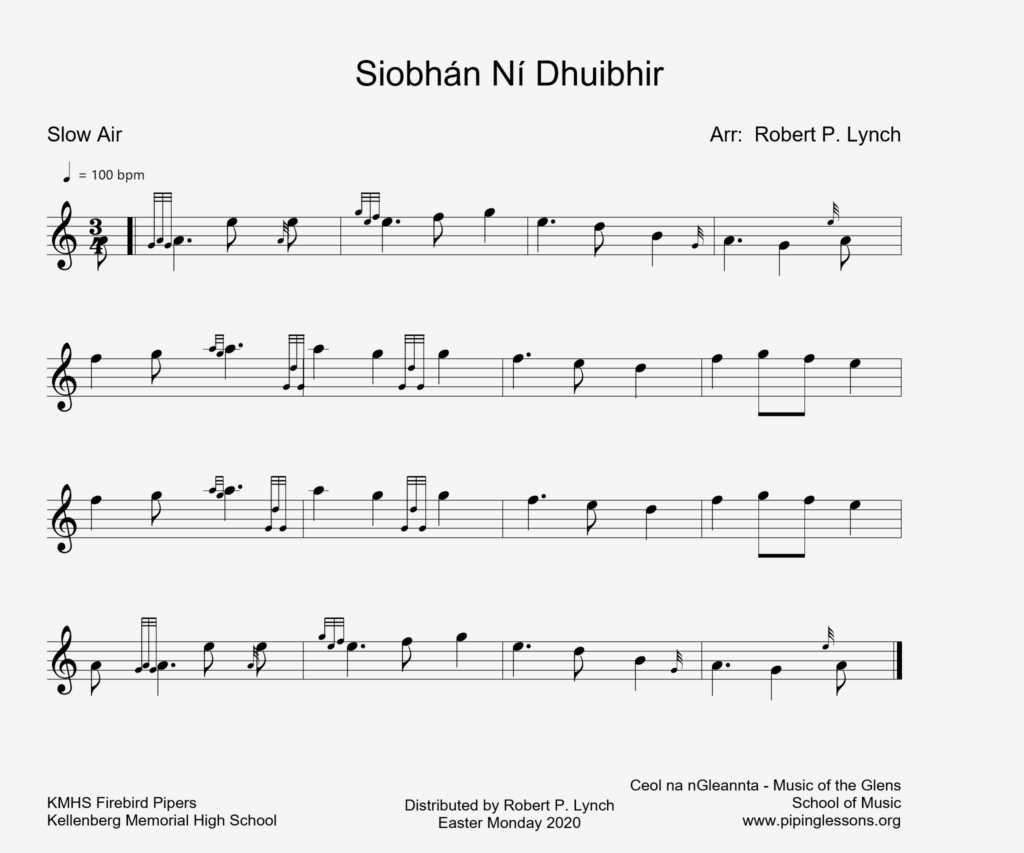

13 April 2020, at the 1916 Monument outside the Nassau County Courthouse in Mineola, on Long Island, NY. The video was streamed online as a substitute, during the Covid-19 crisis, for the annual large gathering which usually take place there on Easter Monday.

Liner Notes for “Stepping on the Bridge”, by Hamish Moore May 1994

Liner Notes for “Stepping on the Bridge”, by Hamish Moore May 1994